Hundreds of huge trading ships called Manila Galleons were once made in the Philippines for intercontinental trades. From 1565 to 1815 (250 years), these ships crossed the vastness of the Pacific Ocean and established a trade between Manila in the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico. These galleons, at that time, were also called “La Nao de la China”, due to most of their cargoes were goods from China.

Hundreds of galleons were produced in the ship building yards of Cavite. These galleons were the biggest of its time, fit enough for long voyages, huge cargo capacity, and sometimes carry hundreds of passengers. It was expected that a trip from Manila to Acapulco would take 4 months. The galleons were equipped with canons and other naval weapons to protect itself from attackers. The trade was very lucrative that the cargoes of the galleons became the interest of pirates and rival colonists.

For 250 years, once or twice a year, there would be a round-trip voyage from Manila to Acapulco by a galleon carrying goods such as rare commodities, luxury items from China, spices, cotton, silk, new technology, and even slaves. Practically, any material that had great value and demand that can be put on a ship was traded. These galleons had a cargo capacity of 700 to 2000 tons. The galleons sometimes also carried important passengers that had significant influences to the Filipinos like missionaries, doctors, scientists, teachers, and architects. The trade enabled an exclusive exchange between Manila and Acapulco of not just goods, but also the benefits of cultural exchange, economic progress, and modern ideas.

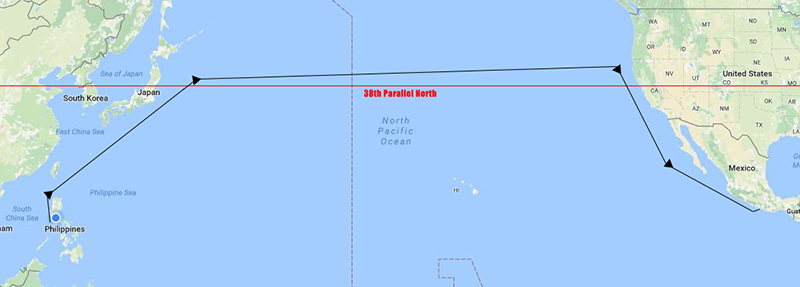

The galleons sailed in the Pacific Ocean through a route discovered by Andrés de Urdaneta, an explorer and a Catholic friar of the Augustinian order. The route, which is later nicknamed “Urdaneta’s Route”, was actually a return route (tornaviaje) for the Spanish colonizers that took advantage of the eastward winds for sail at the 38th parallel north, off the east coast of Japan. The eastward winds blew them back to the western hemisphere. The Spanish kept this route as a secret to gain monopoly and avoid competition against other powers such as the Dutch and English who were also extending their colonies in Asia and the American continents.